I’m a sucker for those library book sales. You know – the ones where you pay a dollar for a hardcover and 25 cents for a paperback.

Usually I pick up novels. Last week at Creighton’s main Reinert Library I couldn’t resist a book called Society without God.

(I expect I was drawn by its cover, a digital composite entitled “Businessmen in desert, rear view” by Marc Romanelli, as much as by its title.

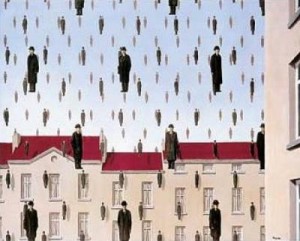

The cover is strongly reminiscent of Rene Magritte’s masterpiece “Golconde,” which I first encountered in law school, where it spoke to me of the law school experience. A print of it now hangs in my office. But I digress.)

Sociologist Phil Zuckerman, author of Society without God, spent a year in Denmark. Conditioned to the pervasive religiosity of the United States, he was amazed by the relative indifference of Danes—and Swedes—to religion and to God, notwithstanding the existence of a national church.

He found these Scandinavians to be culturally Christian, turning to the church for such life events as baptism, confirmation (14-year-olds find it hard to turn down lots of presents!), and funerals.

But actual faith or belief in God? Not so much.

In fact, Zuckerman found religion overall to be pretty much of a non-issue. Danes and Swedes just don’t spend a lot of time thinking about it.

Given the rhetoric in our own country as to the strong connection between religion and morality, between religion and social health and well-being, he was confounded as he realized the degree to which Denmark and Sweden defy the conviction that godliness equates to goodliness.

After all, these two countries rank near the top of so many worldwide indicators of well-being it is difficult to keep track. In 2010, for example,

• In Gender Equity, which I referred to in a prior post, Sweden is at #4 and Denmark is at #7 of 134 countries rated by the World Economic Forum. The U.S. is at # 19.

• In Democracy, Denmark is at #3 and Sweden is at #4 of 167 countries rated by the Economist Intelligence Unit. The U.S. is at # 17.

• On the Human Development Index calculated by the United Nations to capture the well-being of a country’s population overall, Sweden is at #9 and Denmark is at #19 of 169 countries rated by the United Nations. The U.S. is at #4. When inequality is factored in, however, Sweden rises 4 places to #5 and Denmark rises 6 to #13, while the U.S. falls 9 to #13.

Zuckerman’s point as to the many ways in which Denmark and Sweden are flourishing without religion isn’t that religion is bad. Rather, his point is that it isn’t necessary.

Millions of Danes and Swedes live happy, fulfilled, and moral lives without religion. They have taken evolution in their stride; they don’t make a big fuss over either abortion or homosexuality; they face death matter-of-factly; as a society they take care of each other.

Zuckerman points to several possible reasons for the relative religious fervor here in the States. One of them, somewhat surprisingly, is the First Amendment.

In Denmark and Sweden, the Lutheran Church is nationalized and state-supported. Pastors are scholarly, retiring folks who like to get paid to study the Bible and preach every once in a while to a few old folks.

Here, in contrast, the First Amendment prohibits a national church. This creates a situation in which various religions compete for believers.

Zuckerman uses the phrase “aggressive marketing” to describe the result. The images that immediately came to my mind were vendors hawking their wares in a marketplace or the guy who sells peanuts at the ball game.

The First Amendment, in other words, creates religious salesmen.

Salesmen.

I was particularly struck by a comment made by Lene, one of the Danish women Zuckerman interviewed. Lene described a nephew who is being brought up “very Christian.” While she accepts the “nice living rules and stuff” he is taught, she says that “it’s a bit annoying because … he thinks he knows better than us and … he will sometimes scold his grandparents, for example, and other people for not believing.”

I have sometimes wondered if the First Amendment’s guarantee of freedom of speech places an undue emphasis on talking – on telling – rather than on listening.

Could it be that vigorous religious protections have a similar effect?

Could it be that Americans are so caught up in exercising our religious freedoms that we cross the line to telling others not only what they can believe but what they should believe? What they must believe?