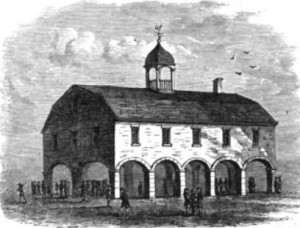

During this week in 1790, the Supreme Court held its first session–meeting in the Merchants Exchange Building in New York City, then the nation’s capital. The Court first assembled on February 1st, but due to transportation problems for some of the justices, the session was postponed until February 2nd.

The U.S. Supreme Court was established by Article Three of the U.S. Constitution, which took effect in March 1789. The Constitution granted the Supreme Court ultimate jurisdiction over all laws, especially those in which constitutionality was at issue. The Court was also designated to rule on cases concerning treaties of the United States, foreign diplomats, admiralty, and maritime jurisdiction.

In September 1789, the Judiciary Act was passed, implementing Article Three by providing for six justices who would serve on the court for life. That same day, President George Washington appointed John Jay to preside as chief justice, and John Rutledge, William Cushing, John Blair, Robert Harrison, and James Wilson to serve as associate justices.

The Judiciary Act also divided the country into 13 judicial districts, which were, in turn, organized into three circuits: the Eastern, Middle, and Southern. For the first 101 years of the Supreme Court’s life, except for a brief period in the early 1800’s, the early justices of the Court were required to “ride circuit,” and hold circuit court twice a year in each judicial district, which was a bit of a hardship given the transportation of the day.

The U.S. Supreme Court grew into arguably the most important judicial body in the world. According to the Constitution, the size of the court is set by Congress, and the number of justices varied during the 19th century before stabilizing in 1869 at nine. In times of constitutional crisis, the nation’s highest court has always played a definitive role in resolving the great issues of the time.

Black robes, but no wigs?

Like their counterparts in the United Kingdom, American Supreme Court justices wear dark robes while sitting on the bench. Wigs, on the other hand, never caught on here in the States. You can thank Thomas Jefferson for that. When Justice William Cushing arrived at the Supreme Court’s first session in 1790, proudly sporting a powdered hairpiece, Jefferson issued a scathing critique of his fashion faux pas: “If we must have peculiar garbs for the judges, I think the gown is the most appropriate. But, for heaven’s sake, discard the monstrous wig, which makes the English judges look like rats peeping through bunches of oakum.”