As has often been noted—in numerous posts on this blog, and by just about any other Supreme Court watcher—that the single most important element of any Supreme Court petition is the questions presented page. This axiom is plain from a reading of Rule 14.1(a), requiring that the questions presented appear on the very first page of the brief, in such an exalted position that “no other information may appear on that page.”

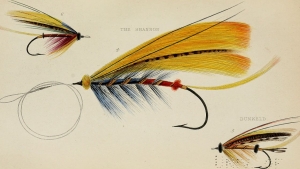

Question Presented: “…the colorful fly that irresistibly leads to a strike.”

The questions presented are a concise statement of the legal controversy the petitioner would like to present to the Court. In the words of Supreme Court scholar Stephen Shapiro, a question presented “should be the colorful fly that irresistibly leads to a strike.” Of course, commentators and Rule 14.1 can tell us what the questions presented should be, but actually achieving a formulation of brevity and intrigue can be excruciatingly difficult.

One concept that might help a drafter find just the right balance is focus. By the time most cases reach the Supreme Court, the controversies have spun along for years, generating thousands of pages of record and argument. Undoubtedly, a petitioner considering a cert petition can point to quite a few perceived injustices throughout the case. And if the party writes a set of questions presented under a belief that the U.S. Supreme Court has been patiently waiting for its turn to jump into the case and assert its vindication on every controversy, the petition will certainly fail.

But a petitioner who uses the questions presented as a chance to focus the Court’s attention down one, two, or perhaps three core issues will have better success. This distillation process will lead to a better-drafted set of questions presented. With focus, the drafter will be able to identify the few, discrete factual and procedural elements of the case that directly bear upon the main controversies. By concentrating on the central legal disputes, other issues that had always seemed to loom large over the proceedings might retreat back into the depths of the record, relegated to incidental occurrences that may or may not warrant a later mention in the Statement of the Case.

The drafter should focus on the core issues, and then identify just those few case circumstances that illustrate the development of those controversies before and during the litigation. If the drafter can focus down to just 200 or fewer words, then she is probably just a few polishing drafts away from a final, compelling set of questions presented.